- Home

- Science

- Science News

- Ruthless, 'Superhuman' Poker Playing Computer Program Beats Professionals

Ruthless, 'Superhuman' Poker-Playing Computer Program Beats Professionals

Pluribus employs a strategy that in some respects affirms the best tactical instincts of the game's top players.

Jason Les, one of the world's premier poker players, was representing his species when he faced off in May against a computer program named Pluribus. The game was multiplayer no-limit Texas hold 'em. Les and other professional poker players with at least $1 million in career earnings volunteered to play the bot to test whether it had reached the elite level of poker virtuosity.

"I was defending humanity's dominance in this game," Les said. "Unfortunately, I failed."

The triumph of Pluribus was reported Thursday in the journal Science under the headline "Superhuman AI for multiplayer poker." Like chess, checkers, Go and other games, the most popular form of poker has now been mastered by the cold, heartless machinations of a computer program.

Pluribus employs a strategy that in some respects affirms the best tactical instincts of the game's top players. But it also has some startling tendencies, including a bewildering unpredictability in its betting habits. It often bets huge sums early in a hand - reminiscent of the disruptive tactics of "Jeopardy!" champion and professional sports bettor James Holzhauer.

This milestone in artificial intelligence has implications beyond poker, or anything happening on the gaming tables in Las Vegas. This technology, the inventors say, could be applied to self-driving cars, auctions, contract negotiations and decisions about product development. It could even be used in political campaigns - helping candidates decide where to allocate resources in a contest with multiple opponents, each with a secret strategy.

Moreover, unlike the "deep learning" AI programs that became unbeatable at chess and Go, Pluribus does not use massive amounts of data and computation.

"The techniques underlying it are very general and I think are going to be applied to a wide variety of settings," said lead author Noam Brown, who works at Facebook Research and is a graduate student at Carnegie Mellon University, where he began this research. The key challenge, he said, is, "How do you get AI to cope with hidden information in a complex, multi-agent environment?"

Tuomas Sandholm, Brown's adviser at Carnegie Mellon and the co-author of the new paper, said the development of Pluribus comes after 16 years of research and incremental improvements in the software. He has started two private companies to commercialise the software, he said.

An earlier iteration of the software program, called Libratus, had demonstrated that it could win at two-player poker, but Pluribus works in a multiplayer poker game, a far more complicated situation. Sandholm described Pluribus as a "depth-limited look-ahead algorithm." Pluribus, in deciding what to do (for example, call a bet, raise a bet or fold), calculates the odds of winning the hand, but it makes calculations only a few steps ahead rather than all the way to the end of the game, which would require implausible amounts of computation. Looking ahead to the end of the game "would take longer than the life of the universe," Sandholm said.

The Pluribus experiment had two phases. First, Pluribus had to get good at poker. It did this by playing hands against copies of itself. It examined what the outcomes might have been had it played differently. If a different move would have improved the odds of winning, the bot would decide to do that move more often. This process enabled Pluribus to hone its algorithm - its "blueprint strategy" - for the next phase, competition against human beings.

The bot played 10,000 hands of poker against more than a dozen elite professional players, in groups of five at a time, over the course of 12 days. In one version of the experiment, five bots played one human. The bots came out on top over time, despite some ups and downs along the way. The researchers calculated that a bot like this, playing with $1 chips, would make more than $1,000 an hour on average from playing poker against top competition.

Some of the best players in the game have already learned from Pluribus.

"One of the strongest suits of the bot is the ability to play mixed strategies. It can have the exact same hand and the same scenario and bet differently every time," professional poker player Darren Elias, who participated in the experiment, told The Washington Post. "You can't pick up a pattern of what he's doing - what it's doing."

One striking trait of this bot is the huge early bet. Sometimes the bot bets the ranch ("all in") early in a poker hand or in a situation where a human probably wouldn't do that.

And sometimes Pluribus folds, even with a decent hand. Or calls a bet even when it has a so-so hand. Pluribus is not afraid to bluff. Most importantly, Pluribus bets in a manner that seems random to human opponents. Unpredictability is the killer app here. And the bot is unemotional and tireless in the strategy's execution. It has the special gift of any machine - the inability to overreact, become discouraged or despair.

"It's unnerving," said Les, 33. "You don't know what to expect. Your preconceived ideas about how humans play poker don't apply."

In Texas Hold'em, each player gets two facedown cards (called the hole cards), followed by three cards placed faceup all at once (the flop), then another faceup card (the turn) and then a final card, also faceup (the river). Players assemble their best hand of five cards from the seven available. There's betting at each round.

In one hand highlighted by the research team, Pluribus had a five and six of diamonds in the hole. The flop showed a 10 and two of diamonds and a four of spades. That looked promising for Pluribus: It could have gotten a straight (good!) if one of the remaining two cards was a three, and it could have gotten a flush (even better!) if one of the final two was a diamond.

Three human players were still in the hand at that point (two others had folded). The first two players "checked," meaning they didn't make a bet but didn't fold. The third human player then raised the pot by $300 - clearly feeling empowered by his hole cards, an ace and a queen. Pluribus had multiple options: fold, call the bet or raise. Pluribus chose the most aggressive move of all - going all-in, betting its entire pile of chips, $9,775. Superhumanly superaggressive! The three human players folded.

Les recalled another hand that Pluribus lost, but which revealed something about the bot. Pluribus had three twos, a pretty good hand, and made one of its typically aggressive bets, three times the pot value, about $3,000 as Les recalls. Then a human opponent went all-in. Pluribus folded.

That sounds like a bad move on its face. Pluribus lost so much money! But the bot didn't care. The bot sticks to a strategy that seems to work inexorably over time even if there are losses in the mix. That includes folding without a worry, and not fretting about lost money. A human would be very reluctant to simply give up on a hand with three deuces and with $3,000 already committed to the pot, Les noted.

"A lot of humans might be, like, 'I've got three of a kind, I've got such a good hand, I can't let this guy push me around.' The AI doesn't have an emotional response like that. It just has a strategy," Les said.

Noam Brown said of his invention: "The bot is always playing the long game. As long as it's right most of the time, it's going to make money in the long run."

One intriguing, or perhaps disturbing, element to the story is that the bot achieves these results without paying attention to the personalities, habits and strategies of its opponents. The bot does not concern itself with human psychology. It doesn't know who it is playing, or try to calculate what the mental state of the opponent might be.

That's in contrast to what's happening this week in Las Vegas at the World Series of Poker. A television viewer will notice that the players spend a lot of time scrutinising each other, trying to figure out who is bluffing and who is not - looking for the "tell."

What Pluribus suggests is that humans may overrate the psychological part of the game. Getting the math and probabilities right seems to be all that's necessary to be a champion.

It doesn't matter who's twitching and scratching and blinking at the table.

© The Washington Post 2019

Get your daily dose of tech news, reviews, and insights, in under 80 characters on Gadgets 360 Turbo. Connect with fellow tech lovers on our Forum. Follow us on X, Facebook, WhatsApp, Threads and Google News for instant updates. Catch all the action on our YouTube channel.

Related Stories

- Samsung Galaxy Unpacked 2026

- iPhone 17 Pro Max

- ChatGPT

- iOS 26

- Laptop Under 50000

- Smartwatch Under 10000

- Apple Vision Pro

- Oneplus 12

- OnePlus Nord CE 3 Lite 5G

- iPhone 13

- Xiaomi 14 Pro

- Oppo Find N3

- Tecno Spark Go (2023)

- Realme V30

- Best Phones Under 25000

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Series

- Cryptocurrency

- iQoo 12

- Samsung Galaxy S24 Ultra

- Giottus

- Samsung Galaxy Z Flip 5

- Apple 'Scary Fast'

- Housefull 5

- GoPro Hero 12 Black Review

- Invincible Season 2

- JioGlass

- HD Ready TV

- Latest Mobile Phones

- Compare Phones

- Apple iPhone 17e

- AI+ Pulse 2

- Motorola Razr Fold

- Honor Magic V6

- Leica Leitzphone

- Samsung Galaxy S26+

- Samsung Galaxy S26 Ultra

- Samsung Galaxy S26

- Asus TUF Gaming A14 (2026)

- Asus ProArt GoPro Edition

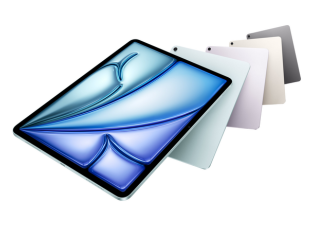

- Apple iPad Air 13-Inch (2026) Wi-Fi + Cellular

- Apple iPad Air 13-Inch (2026) Wi-Fi

- Huawei Watch GT Runner 2

- Amazfit Active 3 Premium

- Xiaomi QLED TV X Pro 75

- Haier H5E Series

- Asus ROG Ally

- Nintendo Switch Lite

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAID5BN-INV)

- Haier 1.6 Ton 5 Star Inverter Split AC (HSU19G-MZAIM5BN-INV)